No Sinless Flags: Thoughts on the Confederate Flag and the Power of Redemption

Jun 24, 2015

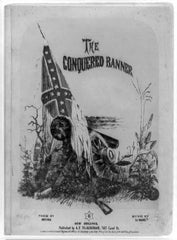

“Furl that banner! True, ’tis gory,

Yet tis wrethed around with glory,

And ’twill live in song and story,

Though its folds are in the dust.” – Excerpt from The Conquered Banner, Father Abram Joseph Ryan, 1838-1886

Television has made a nation of fine spectators. As a kid, growing up in Tennessee during the 80’s, my introduction to the Confederate flag, other than the likely tattooed arm of an uncle, was the Dukes of Hazard. I was so enthralled by the story of these two brothers and their ability to defy the law, as well as gravity, in their ensigned Dodge, that I never considered the historical reference of the emblem boldly presented across the roof of their General Lee. There is a chance, as well, that their sister, Daisy Duke, contributed to my fascination with the show. Come to think of it, we referred to it as the “Rebel Flag”, further distancing it from the Civil War and time period from whence it came.

My introduction to the Civil War, however, was not as puerile, though experienced at that tender age when life so easily imprints itself in the soft earth of boyhood memory. I learned of the Civil War in the classroom, of course, but I am speaking of the time when I really discovered it; when it became tangible, interwoven with my own reality. I must have been about 10, and was taking a field trip with my classmates to Shiloh National Park, the historic site of the Battle of Shiloh.

When we arrived I was excited and disappointed all at once. All along the way there, we had talked about the Bloody Pond where soldiers and horses, on both sides, would come to wash their wounds, many dying at the water’s edge. Imagine my disenchantment when we arrived and found only a pond, no blood. In my naiveté I assumed the blood would still be there, which of course was the attraction. They should have called it the Bloodied Pond, past tense, though I don’t suppose that would gull many youths into visiting. After this there was a small cannon and a field…then another field. This would not do for a boy of 10 and a robust imagination. I asked the guide, “Do you think there are any old bullets or knives or guns around here that no one has found yet?” You could ask these kinds of things in the 80’s without being thought of as a burgeoning psychopath, because Reagan was president and men had testicles.

The guide answered, no, that due to it being over a century ago and the scores of people which had come through the park, there was no chance of finding anything of the sort. No sooner had she dashed my hopes, than I looked down at my feet, and, as the other children in the group began to move on, I stayed, momentarily. My eyes were fixed on something grey, peeking out of the ground and grass. Could it be? It was! I found a lead bullet, heavily dimpled and worn. I thought about not telling anyone because I didn’t want it to be taken from me and put in a museum. I was something of the class-clown and so it took some persistence before the teacher and the guide would believe I had actually found something. The guide confirmed, with astonishment, that I had indeed found a bullet. She let me keep it.

It was as if we were all at the theater, taking in a show, when one of the actors came out from behind the curtains and singled me out and said, “Come with me backstage, behind the scenes, and I’ll show you how all of this works.”

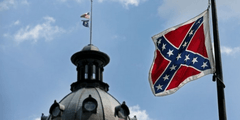

The reaction to the murder of nine innocent people in Charleston is being handled very well by those closest to the tragedy. However, there are those who see this as an opportunity to push forward an agenda, and, misguided as it may be, their rhetoric is not without merit. I am speaking particularly about the opposition to the Confederate flag being flown in South Carolina. I hope to aid in this discussion by persuading clearer heads with impassioned but systematic thoughts on this subject.

Understanding the Arguments

You may already be familiar with the arguments being presented on both sides, those for and those against the Confederate flag.

The Opposition

Those who would like to see the flag banned from public grounds as well as rooted out of society as a whole believe that the Confederate flag is a sore reminder of a Southern slavery and the Confederates bloodied attempt to continue owning slaves. Therefore, the flag is a symbol of inequality and a part of history that should not be celebrated.

The Supporters

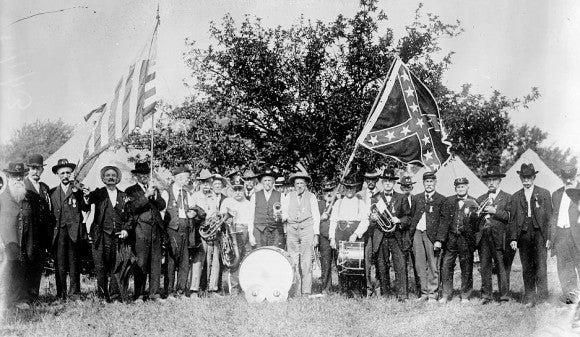

Proponents of the flags continued unfurling, both on public grounds as well as on t-shirts and trucks, argue that the flag is a symbol of the South and its rebellious, fighting spirit. It pays tribute to the soldiers who fought for their rights to live as they pleased and serves as a reminder of that horrible but strangely cherished war.

Why Both Arguments Have Merit and Why Neither Will Settle the Issue

Prior to the Civil War it is estimated that only 5-20% of white Southerners owned slaves. The reason for that wide percentage spread varies and I’m not going to go into detail on that as the information can be obtained easily enough if you are truly interested. Of that percent, only a small percentage owned a plantation of 100 or more slaves. The point in saying this is not to advocate slavery as long as you only have a few slaves, but to point out that, contrary to popular belief, most people in the South had no vested interest in slave ownership, certainly not enough to justify war. Of slave owners, the majority only had a few to help around the house. If slavery was abolished, as it was trending towards, most slave-owning families would not suffer a critical loss like that of the larger plantation owners. Racism and prejudice was certainly wide-spread in the South, though it is easier to objectify and mistreat 100 people who work in the fields, than 2 or 3 who work in your house. That being said, racism was evident in some form across the nation in our early days, especially when we include Indians and Asians.

The idea that all Southerners went to war to continue owning slaves and the North to free them all just doesn’t hold up. So then, why did the South leave the Union and rebel? What did so many men fight and die for? Historians are still asking these questions, but it certainly isn’t a cut and dry as the political pundits and special interest groups make it out to be. Many in the South saw a growing central government that was being increasingly represented by those in the North. There was fear that the values and traditions, not to mention the rights, of the South were being lost. There were disputes over how overseas trade should be handled and pragmatic concerns on both sides on how to deal with a soaring demand of cotton and the abolition of slaves which provided much of the labor.

From Perman and Taylor’s Major Problems in the Civil War and Reconstruction: Documents and Essays:

“Some historians emphasize that Civil War soldiers were driven by political ideology, holding firm beliefs about the importance of liberty, Union, or state rights, or about the need to protect or to destroy slavery. Others point to less overtly political reasons to fight, such as the defense of one’s home and family, or the honor and brotherhood to be preserved when fighting alongside other men. Most historians agree that no matter what a soldier thought about when he went into the war, the experience of combat affected him profoundly and sometimes altered his reasons for continuing the fight.”

These arguments lend merit to the supporters of the Confederate flag as a symbol of the South, of freedom, including the freedom to rebel, and states’ rights.

However, the start of the Civil War can be traced back to those large plantation owners, those with political and military influence and the combined wealth to start and fund a rebellion. They believed that the abolition of slavery would result in a loss of their cheap labor force and made an impulsive move to protect it. The issue of slavery was very real during the Civil War and would have likely continued, though for how long is speculative, should the South had won. This, then, gives credit to those who see the flag as symbol of a disgraced time in American history.

Both sides are choosing to see the Confederate flag through a narrow historical lens which supports an existing narrative and worldview. In fact, the current “Confederate Flag” was not actually a popular flag design until after the Civil War ended.

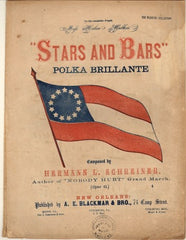

The Confederate “Battle” and “Navy Jack” Flags

The flag we commonly refer to as the “Confederate Flag” is actually the Second Confederate Navy Jack, a rectangular version of the Confederate “Battle” Flag. The original Navy Jack had a lighter blue cross, but other than that it is the same. The red flag with stars and a blue and white cross that we are familiar with was one of the emblems added to the official Confederate Flag as you can see below. Regardless of the varied meanings of the official Confederate States of America flags, the meaning of the battle flag has remained the same:

Red – Represents sacrifice, much like red in the American flag.

White – Represents the purity of ideals.

Blue – Represents justice. The blue on the Navy Jack is lighter than on the original “battle” flags.

Stars – One for each state in the Confederacy.

Cross – The cross of St. Andrew, a disciple and martyr of Jesus. The ‘X’ shape of the cross refers to the story of his crucifixion. Not deeming himself worthy of being crucified on a cross like that of Jesus, St. Andrew requested to be crucified on a cross arranged in an ‘X’ rather than ‘T’ pattern.

The adoption of the Navy Jack by hate groups to represent white supremacy or eternal allegiance to the Confederacy — “The South shall rise again!” — only confirms their ignorance. The red flag we deem the “Confederate Flag” today was a symbol already being used and recognized by Southern armies, which is why it was included in the official CSA flags. After the war, the South began using the Navy Jack (with a darker blue) to represent the spirit of the South and to honor the lives lost in the war.

There are No Sinless Flags

“The flag of the United States has not been created by rhetorical sentences in declarations of independence and in bills of rights. It has been created by the experience of a great people, and nothing is written upon it that has not been written by their life. It is the embodiment, not of a sentiment, but of a history.” – President Woodrow Wilson, 1856-1924

It seems ironic to quote Woodrow Wilson considering the position I am taking as you will see below, but his sentiments are spot on. Old Glory may have been created in the sentimentality of liberty and freedom, but her history is marred by scores of atrocities. At the same time, she represents the continued struggle towards liberty and the Great Experiment that we are all engaged in. Flags are created as an emblem to an ideal, a signpost bidding welcome to men of similar thought and deed, a banner raised high in the collective charge towards a conviction. And, while they may or may not change in appearance, they take on the history of their people, and become greater in meaning than can be easily expressed. They come to symbolize not just an ideal, pure in its infancy, but the reality of it, scars and all.

The Power of Redemption Over Progressivism

When I speak of Progressivism I am talking about the political philosophy which maintains that a better state of existence for humans can be attained through a strong central government and social change. There are leanings in Progressivism towards Socialism and perhaps Communism, but that aside, there are people who believe that progress can be achieved through rules, put in place and enforced by government, and through social pressure to conform society to an ideal, a utopia, rather than reality. We are seeing this social pressure in the case with the Confederate Flag and Charleston. The tools being used are misinformation and shame, neither of which help to develop a society I long to live in. The idea is that if people are taught what is offensive (misinformation), they will stop offending. If they don’t believe the misinformation, shame or fear of being thought ill of will keep them in line.

This is an old game and one that Christians should be familiar with.

This is where redemption comes in. There is incredible power in redemption, especially the kind done through sacrifice and forgiveness. The cross itself, once a symbol of torture, is now a sign of life and peace everlasting. When Nordic Vikings were introduced to the Gospel and became Christians, the runes that once represented their paganism were used in clever ways to represent converts. The Bloody Pond at Shiloh, disappointing though it may have been, is a place of remembrance, hallowed by the men who gave their lives and the many people who have come to pay their respects.

I don’t know whether or not the current version of the Confederate Flag needs to be redeemed but, it can be, and, perhaps already has, as we see its adoption as the “Rebel Flag” and emblem of the South. Be it old or new meanings that are being applied, what it represents now to its supporters is far more indicative of a people who have “progressed” than those who hold to old and false views.

Final Thoughts

When I found that bullet in Shiloh, I didn’t care which side it came from. It could have been shot from a Union rifle at a Confederate soldier, or simply dropped on the ground by either party. I was impressed by the struggle itself and by the men who could have gone through such a terrible battle as to die in a shallow pond, tending to their wounds. Honoring the fallen and acknowledging their heroism does not mean agreeing with all they fought for. In the same way, flying a flag does not mean its history is still as pure as its ideals. Those who seek a sinless flag to follow will find it unfurled above the heads of dithering philosophers. Those who seek a genuine banner, scars and all, will find it in the company of men.

Have any thoughts to share? Do so in the comments below, or on social media!

“Furl that banner! True, ’tis gory,

“Furl that banner! True, ’tis gory,  “The flag of the United States has not been created by rhetorical sentences in declarations of independence and in bills of rights. It has been created by the experience of a great people, and nothing is written upon it that has not been written by their life. It is the embodiment, not of a sentiment, but of a history.” – President Woodrow Wilson, 1856-1924

“The flag of the United States has not been created by rhetorical sentences in declarations of independence and in bills of rights. It has been created by the experience of a great people, and nothing is written upon it that has not been written by their life. It is the embodiment, not of a sentiment, but of a history.” – President Woodrow Wilson, 1856-1924