Traditional Archery: Part 1 – Recurve and Longbow Fundamentals

Nov 24, 2015

As a young boy, I remember heading off into the woods to find the perfect “D” shaped limb or sapling to use to make my own bow, thinking that since all of the bows I had ever seen on T.V. were of that shape there must be trees that grew this way. It didn’t take long for me to realize this was not the case and that what I actually needed was a straight limb that had a strong dislike for being bent. Apparently the power of the bow came not from the string being pulled back, but rather the wood doing its best to snap back to its original, straight position. I was soon on my way to launching arrows at trees, birds, and, on occasion, friends. And so, as many things tend to be in our boyhood, when the mind opens a window the heart lets in the fresh air, and it changes our inner rooms forever, and my fascination with that stick and string would be with me well into adulthood.

Most men are enamored with the bow and arrow. Where we find the earliest remnants of man, we find this primitive weapon, and over the millennia it has scarcely been improved. Though the compound bow has recently become a favorite, it is really in a class of its own. Many hunters and archers are finding the joy that comes from the challenge of shooting and hunting with a traditional bow such as a recurve or longbow. The instinctive nature of the draw and release, the simplicity of the instrument, the vast assortment of woods and designs, and the history of the bow all make for a powerful pull on the modern man.

It seems fitting to start this series on the week of Thanksgiving, harkening back to the times of the Indians and their many hunts which inspire men to this day. Though the traditional bow can be relatively simple in design, there is still quite a bit to know in order to be an effective bowman and a good deal of history in the evolution of the classic weapon which will make you appreciate it all the more.

Getting Started with Traditional Archery

When we talk about a “traditional bow” or “traditional archery” we are speaking of non-compound bows or non-mechanical bows. This term can refer to a simple stick and a string or a fiberglass laminated takedown. For the traditional bow there is no sight or aiming, every shot it taken instinctively (more on that later). This adds to the learning curve but also the appeal and freedom to shoot as you see fit, rather than as the bow is fitted which is the case with compound bow. From this instinctive style of shooting come so many of the trick shots we see in competitions and a sense of overall mastery with the bow.

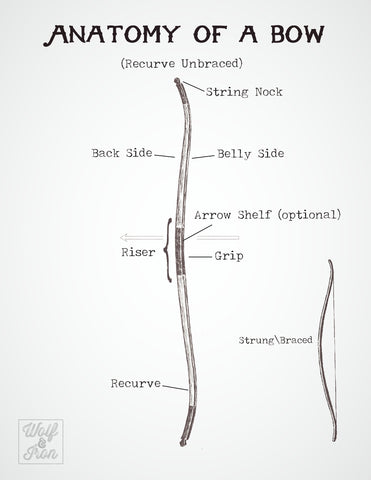

The Anatomy of a Bow

Below is a quick guide to the parts of a bow you should be familiar with (click for larger).

The Anatomy of a Traditional Recurve Bow. Pictured is a simple recurve, a truly primitive weapon and hunting tool as used by early Native Americans.

Pounds and Draw

There are two numbers that apply to both traditional and compound bows: pounds (lbs or most commonly ‘#’) and draw (or draw length). The # represents the number pounds of force required to bring the bow back to full draw. Unlike a compound bow, a traditional bow does not have a “set” draw length which more or less locks the string in place and relieves the tension for the archer. Rather, a traditional bow has a relative pounds for the length of draw.

For example, a bow set 55# at 28″ (or 55@28) would require 55lbs of force to bring the string 28″ from the belly-side of the grip. However, a person who is shorter or prefers a shorter draw and may typically pull the string back to only 26″ would require less than 55lbs of force to draw the string. The result is that the bow would not release the arrow with the same force, but this may be of no consequence to the archer having become instinctively use to shooting the bow.

Longbow vs. Recurve

I have noticed that when hunters talk about “traditional” bow hunting they often use the words “traditional” and “recurve” interchangeably. The recurve style of bow has long been a favorite of hunters and archers so it is no surprise that it has become synonymous with the sport. However, there are two styles of bow most often used in traditional archery: the longbow and the recurve.

The Longbow

A longbow in full draw. Notice the “D” shaped limbs. When unbraced the bow would simply be straight.

The Longbow gets its name from the length of the bow. Because of its simplistic design, the bow relies solely on the strength of its limbs, meaning their thickness and length. It is not uncommon for a longbow to be as long as the archer is tall, if not more so. Ancient English longbows, typically made of Yew, would often have a draw weight well over 100lbs. That means he would have to enlist 100+lbs of force, hold the position until ready to shoot or given the command to release, and repeat. In comparison, it is legal in North Carolina to hunt deer with a 40# bow. Other cultures, however, were smarter about their bow design and enlisted various styles of recurves.

The Recurve

Harold Groves, 1959 shooting a recurve. Notice the arc at the top of the limbs facing away from the archer. Notice also the thick “grip” on the bow.

The recurve had been a part of bow history for quite some time before English archers took it up. The upper limbs curve away from the archer, increasing the strength of the bow by over 10% while reducing the length. I’ll do my best to explain how this works. A typical limb wants to return to a straight position, right? It will exercise all of its force to come back to straight, prevented only by the string, thus transferring the force to the arrow being launched. A recurve wants to go past straight, thus more force is exercised by the bow to return to forward-facing curve. More energy is stored in the upper limbs than a longbow of comparable length.

As bows were being re-introduced into American society after the winning of the west and taming of the wild, the recurve quickly became the popular style. While men such as Saxton Pope and Art Young revived the sport in the early 1900’s, it was Fred Bear who brought the bow, and the recurve in particular, to the market.

Fred Bear and a grizzly he took with his recurve. Mr. Bear would film his amazing hunting adventures and before long, men and women across the country were lining up to get their bows.

Stay Tuned

Over the next few articles in this series we’ll cover shooting, hunting, arrows, wood types, and more.